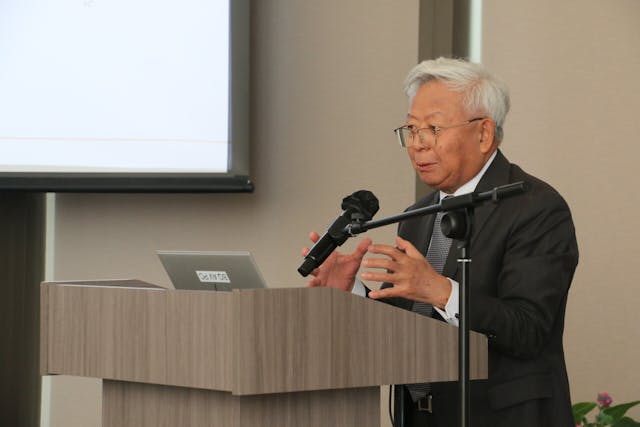

由香港大學當代中國與世界研究中心(CCCW)與黃廷方慈善基金聯合主辦的首屆富麗敦論壇(Fullerton Forum)於1月13日,在香港富麗敦海洋公園酒店舉行。論壇吸引逾60位來自學術界、商界及政界的重要嘉賓出席,包括香港特區前行政長官林鄭月娥、國際清算銀行亞太地區首席代表張濤、外交部駐港公署副特派員李永勝,以及知名企業家與學者李開復、馬駿等。

亞洲基礎設施投資銀行(AIIB,下稱亞投行)行長金立群為首場論壇的重磅主講嘉賓,發表了題為「全球挑戰與多邊主義」的演講,呼籲推動全球治理改革,並強調香港在支持可持續發展和國際合作的關鍵角色。

多邊主義是全球治理的基石

金立群指出,當前國際社會正面臨政治、經濟及環境等多重挑戰,包括地緣政治衝突、貿易保護主義、高利率對全球經濟的壓力,以及氣候變化的威脅。他批評現有全球治理機制無法應對這些困境,並認為亟需通過深化多邊主義來強化國際合作。

他強調多邊主義是全球治理的基石,但當前國際機構在運行方面仍存缺陷,例如雖然國際貨幣基金組織(IMF)和世界銀行等布雷頓森林體系的機構貢獻了經濟穩定,但其治理結構未能隨全球權力格局的變化而調整,導致發展中國家的訴求未被充分反映。

呼籲重新分配國際治理中的權力與責任

金立群強調,當前的國際規則仍由二戰後的主要經濟體制定,許多發展中國家在制度內缺乏話語權,故重新分配國際治理機構內的權力和利益是當前的迫切需求。他認為缺乏問責和權力的不平衡,是現有國際機構低效和內部分歧的主要原因;許多成員國只關注自身利益,無法形成統一立場。這種局面不僅加劇了全球挑戰,還使問題無法解決,甚至惡化。他呼籲重新分配國際治理中的權力與責任,通過創新的多邊機制提升各方的參與度與公平性。

至於重塑國際權力分配的過程,金立群認為新興的多邊機構(如亞投行)可以補充傳統國際機構的不足。亞投行通過創新運作模式,賦予發展中經濟體更大的話語權,同時與世界銀行和亞洲開發銀行等機構密切合作,為基礎設施發展提供更多資金支持。他還提到,亞投行在促進可持續融資和吸引私人資本參與方面,取得了重要進展。

香港在多邊主義中扮演什麼角色?

在談及香港的角色時,金立群高度評價了香港在推動多邊主義和可持續發展的作用。他提到香港作為亞洲基礎設施資產證券化市場的樞紐,正成為推動地區經濟轉型的重要力量,特別是香港交易所推出的國際碳市場,為可持續發展提供了創新的解決方案。

此外,亞投行與香港合作推動基礎設施資產證券化,將香港定位為亞洲債券與證券化市場的重要參與者,未來還將繼續支持香港在綠色金融及區域合作方面的發展。

金立群在演講最後表示,儘管全球挑戰層出不窮,但他對未來保持樂觀,並期待與香港及其他地區合作,推動多邊主義和全球治理改革,共創更加可持續和包容的未來。

本社獲授權特別轉載亞投行行長兼董事會主席金立群演講原文,以饗讀者。演講全文如下:

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is my great pleasure and honour to be invited to this meeting.

Anybody can give you a list of the major challenges faced by the international community today. Politically, there have been military conflicts going on here and there, refuges as their collateral damages, and threats of nuclear war are raising its ugly head behind the screen. Economically, we are faced with persistent high interest rates, slowdown of many economies, mounting protectionism, trade disputes, hurdles to cross-border investments imposed on all kinds of ridiculous excuses. On top of these problems, we face a host of environmental issues, loss of biodiversity, pollution and the consequential health hazards, recurrent pandemics, and climate change. In today's world, many natural disasters are not truly natural. These troubles are anthropogenic, that is, caused by the humans themselves.

As the global challenges are taking a heavy toll of many economies around the world, the world seems to be falling apart. Against this background, there is now a trend gaining fierce momentum: anti-globalization, anti-free-trade, and anti-cross-border investment. And with many deafening noises, we have mantras for decoupling and delinking heard daily above the din.

But then, what is the biggest risk, out of all these menaces, facing us today? The most austere risk is undoubtedly the lack of governance, that is, fully functioning global governance, a deficiency deplorably suffered by the international community. Global governance has to be built and fostered on the basis of multilateralism, and unqualified multilateralism for that matter.

People tend to live in dreams. As the Irish poet W.B. Yeats says, lyrically, "In dreams begins responsibility." This timeless observation invites us to reflect on the immense responsibility that comes with envisioning a better world. Our gathering here at the Fullerton Forum—a space dedicated to understanding the nexus of contemporary China and the world—offers us a chance to reaffirm our collective dream of a world bound not by divisions but by mutual trust, cooperation, and shared prosperity.

The year 2024 witnessed the 80th anniversary of the Bretton Woods, which ushered in a new round of multilateralism.

One has to in fact trace a little more backwards to fully date the beginning of multilateralism. The League of Nations was set up after the first world war at Versailles conference. It was not successful in preventing the outbreak of the second world war, but the League did lay the foundations for the institutionalization of global affairs in the modern era.

Over the last eight decades, multilateralism has been moving forward on a bumpy road over these years, and it is not robust enough to forge a global governance structure fit for the contemporary world. This does not deny the fact that the Bretton Woods institutions have played significant roles over the last 80years. These bodies—IMF, the World Bank, and others— have stood as beacons of international cooperation, shaping decades of economic stability and growth.

Notwithstanding such achievements, multilateral institutions are faced with challenges. Lack of global governance does not mean that we do not have governance at all. The United Nations, WTO, the Bretton Woods institutions and most of the other multilateral development banks and international financial institutions all function as global institutions, and thus the running of these institutions reflects global governance. Their organizational structure, functioning, and management are based on the consensus of those who establish them and their followers who carry on the tradition. In essence, these global institutions are multilateralism incarnate. What is crucially needed is robust multilateralism which can underpin the global governance.

When it comes to problems which are on a global scale, people normally turn to those institutions for answers to their questions and for solutions. Obviously, and perhaps increasingly over the recent years, those institution people appeal to when they have a problem do not seem to be able to work satisfactorily as they are expected. And disappointment is more often than not a common sentiment. Under such circumstances, the rules of game made more than half a century ago are now being challenged, sometimes by none other than the participating countries who made and have championed those rules, until very recently.

Institutions are only as good as its individual members who make up the institution. Not every member will think and behave the same way, often driven by their own interests. But the members of the international community are obligated to observe the basic principles and rules for the common interests.

Climate change, pandemic, trade and cross-border investments, demographic issues, etc. are all of them global issues, but the institutions which are created to address them are sometimes very much divided, because the decision-makers thereof do not see eye to eye with each other, and they can hardly find themselves on the same page. Indeed, they are fighting for their own interests, some are justified and some others are not, and consequently the problems are accumulated and come to the point of no return.

It is known to all that most of the international institutions, such as the UN, the Bretton Institutions, WTO and its former incarnate General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade or GATT, were set up with the rules of games made by the major partners at a time when the minor ones, the backbenchers, had no roles to play. Most of the developing countries had no voice in the global political and economic affairs, and quite a number of them were still colonies of some developed countries. Over the last eight decades, the economic might of a number of emerging economies has been steadily on the rise, and balance of economic and political power has dramatically changed. Under such circumstances, redistribution of power among the members of these institutions has become a major issue, with some demanding a change and some others resisting.

The fundamental reason is lack of accountability. And the global institutions whose mandate is to work out global challenges are lacking in their authority, with no binding rules to follow. Or even there are rules considered binding, they are not enforced. Some people can choose to ignore those rules with impunity. Sovereign power in this world trumps that of the international organizations.

It is high time that we tried our best to fix the global governance problems. Fundamental reforms will have to be undertaken. The present-day world is not the same as what it wasin 1944. There is now a large group of emerging market economies with increased economic might, often combined, in asserting their interests and demands. These countries ask for a voice in reshaping the global governance structure, and in the rebalancing of the interests among all the stakeholders. Their demands should be seriously and reasonably considered and their interests be protected. Compromise is definitely necessary in the broad interests of the international community. In some cases, it seems that problems experienced by only a few members could eventually turn out to be a big problem affecting all. This is what we have seen in the backlash against globalization. The problems and difficulties the vulnerable and marginalized people have experienced are quite often serious, and will fester, becoming eventually major factors that caused troubles for the society in its entirety.

Throughout this process, there are some new institutions which came to be established with new rules of game in a bid to supplement the reform efforts made by the legacy institutions. Those new multilateral institutions are charged with the responsibility to deal with a host of issues faced by the international community, and some are urgent ones as follows:

• Rising economic shares and increasing competitiveness of many aspiring developing economies, yet still unable - and often times not allowed by incumbents - to fully take over leadership roles in global governance or provide global public goods.

• Pandemic expenditures, aging demographics and stagnating economic growth in many developed economies have resulted in stretched fiscal resources. There is often insufficient fiscal capacity to tackle domestic challenges, let alone directing resources towards developing countries or for global needs.

• Much more significant resources are needed to tackle critical global challenges, including climate change mitigation and adaptation, pandemic preparedness, environmental degradation etc.

• Geopolitical fragmentation which makes the problems referred to above even more serious.

Who should bear the burdens of large transition costs? Are border carbon taxes adjustments fair? More broadly, are industrial policies or even the so-called green industry policies beneficial for the global economy or just beggar thy neighbors? How to regulate AI?

These are some of the issues that continue to create some tensions amongst policy makers. Policy coordination across economies is sorely needed across this range of thorny issues, but it all boils down to political understanding and mutual goodwill.

AIIB was conceived in late 2014 and came into operations in 2016. To be fair, AIIB cannot and does not solve all the global challenges briefly mentioned here. However, AIIB brings in new elements into today’s existing multilateral set up.

• We have an ownership structure that gives greater weight to developing economies, particularly those in Asia. It gives developing members a stronger say in the policies and strategies of the Bank. Yet many advanced economies are also members (with smaller shares) but provide critical inputs, resources, and guidance for the Bank’s operations. We take standards very seriously but take care to avoid putting our strategies ahead of members’ realities.

• We have a business model that relies less on traditional donor driven concessional finance (given the already stretched fiscal resources of many members including in advanced economies). We rely instead on generating more income from private sector operations, including investing in capital market instruments, for our longer-term financial growth which at the end of the day would be for the benefit of developing economies. Instinctively, we are thus very keen to work with the private sector as a result, for our own business model, and also to mobilize more private capital for development.

• We work closely with existing institutions. We are the largest co-financers with the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. AIIB’s policies allow us to rely on the policies and frameworks of these partners. We thus add financing capacity to the global community but avoid burdening members with more requirements, while upholding high standards at the same time.

• By working with various institutions and local partners and through higher efficiencies, we achieve a leaner, more nimble and lower cost model. Today, AIIB has around 700 full staff members with almost USD60 billion financings approved. Unlike some institutions, we also welcome staff from non-members. We have a non-resident Board of Directors that provides key strategic guidance but leaves operations to management.

• We aim to be innovative and push the boundaries of development finance where possible, even in the context of a fairly complex organization with many stakeholders. We have supported capital markets, including financing the securitization of infrastructure assets through Singapore and Hong Kong. We have created a venture equity pool to direct investments into startups that have the potential to bring new solutions to climate change mitigation. We are beginning to see nature as infrastructure and are willing to provide finance towards nature restoration. We also invest in health and social infrastructure.

Finally, I would like to comment on the role of Hong Kong in promoting multilateralism and global governance. HK SAR’s membership in ADB and AIIB is well recognized as an important shareholder in these multilateral development banks. Hong Kong has contributed substantially to AIIB over the first decade of its operation, and I am sure that HK will continue to play a significant role moving forward.

Hong Kong is one of the regional (or global) sustainable financing hub. For example, HKEX (Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited) launched an international carbon market, which is the world's only carbon market to offer Hong Kong dollar and Renminbi settlement, for the trading of international voluntary carbon credits.

AIIB and Hong Kong SAR can work together to support net-zero transition agenda of regional members, including mainland China.

AIIB played the role of an anchor to support HKMC (Hong Kong Mortgage Corporation) to develop Infrastructure Asset Back Securitization Market (IABS) . More commonly known commercial real estate backed securitization, IABS is a niche market segment. This program would greatly raise Hong Kong’s profile in Asian bonds and securitization market.

Looking forward, we are fully confident about the future of HK, and we are deeply committed to working with HK to promote the broad interests of the people here in the other countries in this region, and beyond.

Thank you very much!

______

Speech as given by Dr. Jin Liqun, President and Chair of the Board of Directors of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank at the inaugural Fullerton Forum co-hosted by the Centre on Contemporary China and the World (CCCW) and the Ng Teng Fong Charitable Foundation (NTFCF) at the Fullerton Ocean Park Hotel Hong Kong on January 13, 2025.