中文撮要:美國總統特朗普去年發表他上任以來首份國家安全戰略報告,將中國視為「戰略競爭對手」,最近又宣布對所有進口鋼材和鋁材徵收高關稅,從美國的角度看,美中全面「貿易戰」一觸即發。不過,作者認為,中美之間不會發生全面貿易戰。即使貿易摩擦會對全球貿易和亞太投資產生影響,對中國而言,影響也將小於特朗普的預期。

「特朗普和許多美國官員似乎認為,中國仍然極度依賴外貿增長,金融體系也很脆弱,只要美國的單方面施壓,便可逼使中國屈從」。作者認為,白宮高估了自己逼迫中國的能力,且對中國經濟結構的理解過時,因為中國已從出口主導轉內需主導,並帶動經濟增長。只要中國仍是全球增長最快的經濟體,其市場規模加上增長動力,吸引力將大於美方對「不公平競爭」的投訴和對擔心技術資料洩露的恐懼。

Sino-US economic conflict is on the rise for strong reasons from the US perspective. Late 2017 saw the release of US strategy documents on national security, defence and trade, all of which for the first time defined China as a strategic competitor and disavowed America’s long-standing policy of constructive engagement.

My view remains that there would be no full-scale trade war between China and the US. But even trade frictions could have long-term impact on global trade and investment flows and the political power balance in Asia-Pacific. The short-term effects are likely to be unevenly distributed across the global markets. The impact on China may be much less than what US President Trump thinks, but the collateral damage on the Asian regional economies could be large. This has asset allocation implications on the regional markets.

The stubborn US trade deficit with China

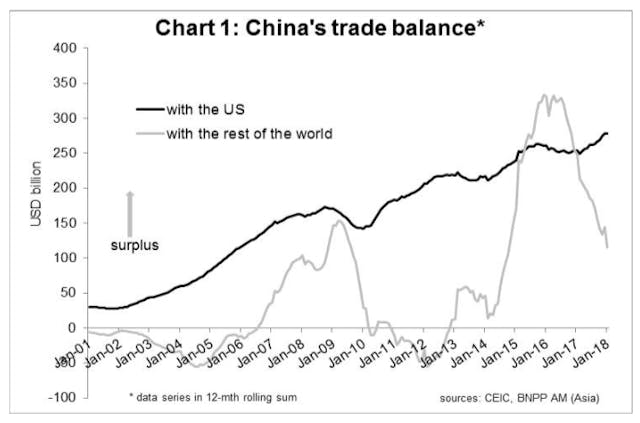

The pressure point of Sino-US trade frictions lies in the stubborn US trade deficit with China. It is more than five times larger than the US’s second largest bilateral trade deficit with Mexico. Furthermore, China’s trade surplus with the US has climbed to record highs while its surplus with the rest of the world has declined (Chart 1).

So President Trump has a strong justification for pressing a tough trade stance against China, and things seem to be moving in that direction. After imposing import duties of 30% and 20% on solar panels and washing machines, respectively, in late January this year, the US Commerce Department proposed in mid-February to impose high tariffs or quotas on US imports of steel and aluminium (China is the world’s largest producer for both commodities).

The collateral damage

The markets see these moves as a vindication of the Mr. Trump’s protectionist policy. However, gross trade data can be misleading because over a third of China’s exports, including to the US, are foreign value-added content mostly produced by other Asian countries.

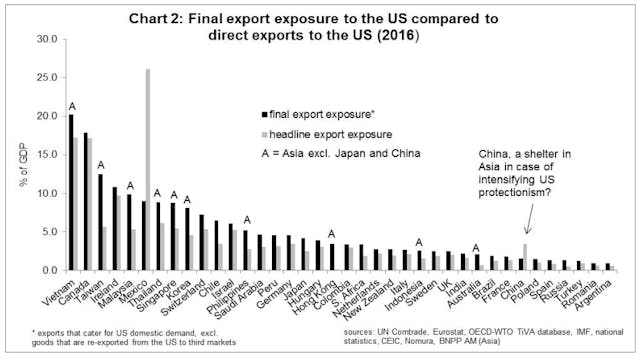

This means that rising US protectionism, as manifested in Sino-US trade frictions, could hurt other economies that supply parts and components to China. The potential collateral damage can be estimated by stripping out the foreign value-added content in China’s gross exports and reassigning them back to its original source countries to assess their ultimate export exposure to the US.

The point is clear: An escalation of US trade protectionism would be quite damaging to most of Asia’s export-oriented economies, with six of the top 10 most-exposed countries being Asian (see Chart 2). The damage on China is rather limited. From an asset allocation perspective, all other things being equal, China seems to be the least affected Asian market in case of a rise in Sino-US trade frictions.

A recent market study also finds that of the most-US-exposed Asian countries, the industries that could be hit by US trade measures are textiles, leather and footwear in Vietnam, computers and electronics in Taiwan and Malaysia and chemicals and petroleum products from Singapore.

The US’s strategic calculations

The US does not seem to be bluffing. In 2017, the US’s trade policy was subordinated to the goal of gaining China’s help on dealing with the North Korean crisis and passing a tax cut bill. Now with the North-Korean crisis risk stabilising and the tax bill passed, tough trade policy has taken priority in Mr. Trump’s political agenda.

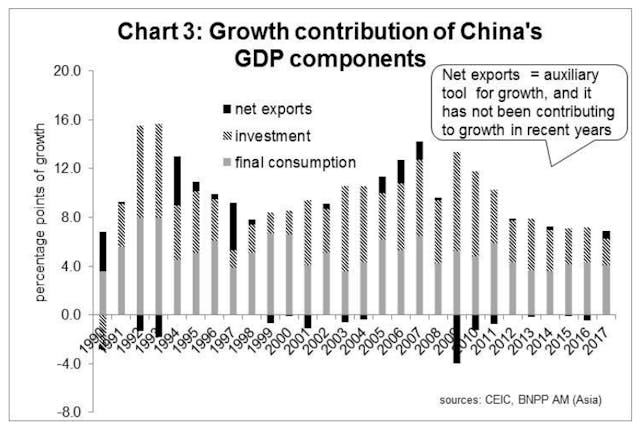

Mr. Trump and many US officials seem to think that China still depends heavily on foreign trade for growth and has such a fragile financial system that unilateral pressure from the US could force China to cave in to American demand. They have overestimated America’s ability to force China’s hands and their understanding of China’s economic structure is outdated, in my view. Since 2009, net exports’ contribution to China’s GDP growth has largely been zero or negative (Chart 3), suggesting that its economy has already shifted from export-led to domestic-led growth.

The reality of China

Market research suggests that a permanent 10% fall in China’s exports to the US would cut Chinese GDP by about 0.3 percentage points. This is material but can easily be offset by domestic infrastructure spending and/or increase in Chinese exports to other markets under the Belt & Road initiative.

Furthermore, the power of China’s domestic innovation to generate growth has improved significantly. Its industrial upgrading process under the “Made in China 2025” industrial policy has been backed by hundreds of billions of dollars in government venture-capital funds in addition to traditional subsidies.

The question to most foreign investors is that with an opaque system with onerous regulations and lack of market access, do they still want to pour money into China? China’s FDI rose by almost 10% to USD144 billion in 2017, according to the UN, when the total amount of global FDI fell by 16% to USD1.52 trillion. Chances are that, so long as China remains the world’s fastest-growing big economy, the lure of its market size and momentum together with economic reform progress will outweigh the complaints about an uneven playing field and the fear of technological leakage.

The risks

In the short-term, a persistent US campaign of economic pressure on China would bolster the view that the US is on a long-term fight to reduce its trade deficit possibly using a weak USD as a tool. US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin raised exactly this fear in late January by commenting on the benefits of a weak dollar. Though senior US officials hastily reaffirmed a strong dollar policy afterwards, the market has grown sceptical because cutting the trade deficit is now a stated policy goal of Mr. Trump and a US think tank research shows that cutting the US current account deficit from 4% to 2-3% of US GDP would require a 10% depreciation of the US real exchange rate.

In the longer-term, both China and the US seem to be striving for on-shoring the globalised production chains built over the past three decades, with China doing it through import substitution to minimise the foreign share of its industrial base and the US via America-first policies. Even partial success of these initiatives could be damaging.

Firstly, the breaking up of the global supply chains will likely bring back inflation by reversing the disinflationary forces brought about by globalisation. Secondly, and arguably, cross-border production chains are a force for peace and stability as they raise the cost of armed conflicts. Reverting back to national production structures raises the possibility that big countries would try to settle their differences by force. It may be too early to be alarmed, but the direction is worrying.

Complication for Asian currencies

Overall, Asian currencies are exposed to US protectionism risk. This means that they would face depreciation pressure as trade slows and local policymakers shift to expansionary policies to protect growth. However, if the USD remains weak despite the expected Fed rate hikes, it would mitigate the protectionism risk on the Asian currencies and would even allow the Asian central banks to lag the US Fed in raising interest rates.

The relative strength of these two forces is unknown. Much depends on the USD’s direction which, in turn, depends on whether the Fed would raise rates by more than expected.